Torque vectoring, braking regen and other unsung EV tech

VECTORING

Torque vectoring is fundamentally different in electric vehicles (EVs) compared to combustion supercars because it shifts from a mechanical process of redistributing existing power to a digital process of creating independent forces at each wheel.

In a combustion supercar (like a Ferrari F8 or Lamborghini Huracán), torque vectoring relies on a complex "mechanical orchestra" of clutches, gears, and hydraulic fluids.

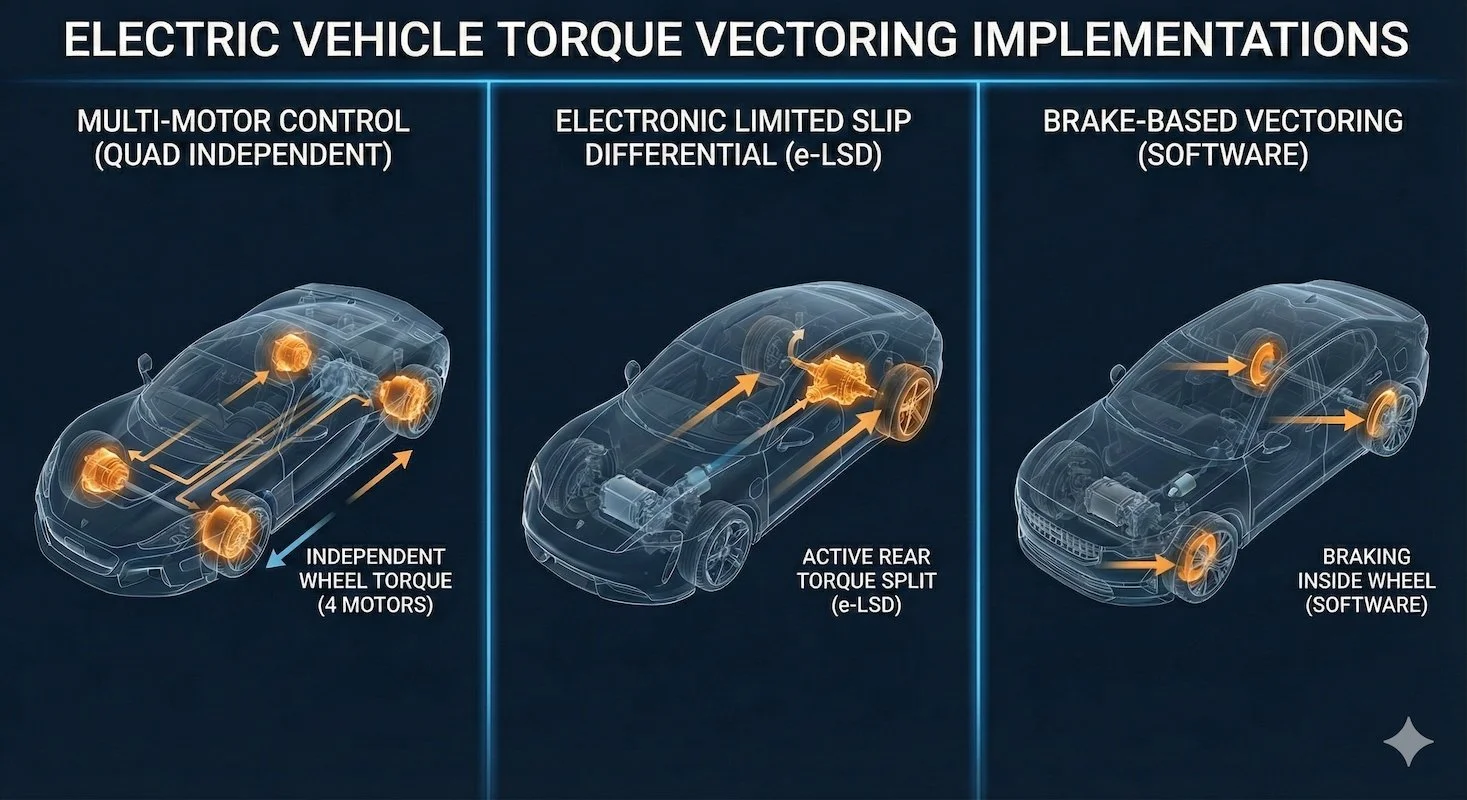

However even in EV’s, not all "torque vectoring" is created equal and there are 3 highly distinct implementations:

Broadly, these systems fall into three categories: Multi-Motor Control, Electronic Limited Slip Differentials (e-LSD), and Brake-Based Vectoring.

Response Time: Multi-motor systems are the fastest, as they don't rely on mechanical clutches or brake pads to engage.

Efficiency: Brake-based systems are technically "wasteful" because they convert kinetic energy into heat to turn the car. Multi-motor systems are "additive," meaning they speed up the outside wheel to help you turn.

Regenerative Vectoring: Only multi-motor systems (like the Rimac or Lucid) can perform "negative torque vectoring," where the inside wheel generates power back into the battery while the outside wheel consumes it to push the car around a bend.

1. Multi-Motor Implementation (The Gold Standard)

This is the most advanced form. By placing independent motors on the same axle (usually the rear), the car can speed up the outside wheel while simultaneously slowing down (or even applying regenerative braking to) the inside wheel.

| Model | Setup | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Rimac Nevera | 4 Motors | Uses “All-Wheel Torque Vectoring” (R-AWTV). It calculates the precise torque for each individual wheel 100 times per second. |

| Rivian R1T / R1S (Quad) | 4 Motors | Each wheel is completely independent. This allows for “Tank Turns” (theoretically) and extreme precision in off-road rock crawling. |

| Lucid Air Sapphire | 3 Motors | Twin rear motors provide 1,200+ hp. It uses the rear motors to pivot the car, allowing it to turn more sharply than its wheelbase suggests. |

| Tesla Model S / X Plaid | 3 Motors | Dual rear motors manage torque across the back axle. Tesla focuses on high-speed stability and corner-exit acceleration. |

| Audi SQ8 e-tron / e-tron S | 3 Motors | One of the first mass-market triple-motor setups. It can send nearly all rear torque to a single wheel in milliseconds. |

| Maserati GranTurismo Folgore | 3 Motors | Uses three 300kW motors. The rear motors are entirely decoupled, allowing for massive torque differentials to tuck the nose into corners. |

| Yangwang U8 / U9 | 4 Motors | BYD’s luxury brand uses four independent motors (“e4” platform) capable of 360-degree tank turns and maintaining stability even with a tire blowout. |

2. Mechanical/Electronic Differential (e-LSD)

These cars typically use two motors (one front, one rear) but include a specialized mechanical or electronic differential on the rear axle to shift power side-to-side.

Hyundai IONIQ 5 N: Uses a dual-motor setup with an Electronic Limited Slip Differential (e-LSD) on the rear axle. This allows it to mimic the feel of a rear-drive drift car while maintaining AWD traction.

Porsche Taycan (with PTV Plus): Uses Porsche Torque Vectoring Plus. It combines an electronically controlled rear differential lock with targeted braking interventions.

Audi RS e-tron GT: Similar to the Taycan, it uses a rear-axle differential lock to vary torque between the rear wheels.

3. Brake-Based Vectoring (Software defined, the most common)

This is what the Jaguar I-PACE and many others use. It relies on the car's "brain" to apply the brakes to specific wheels. While effective for safety and "tucking" the nose into a corner, it is technically a subtractive process (it slows you down to help you turn).

Jaguar I-PACE: "Torque Vectoring by Braking" is standard.

BMW i4 M50 / iX M60: Uses "Actuator Contiguous Wheel Slip Limitation" (ARB). It’s an incredibly fast software-based system integrated directly into the motor controller rather than the separate DSC unit.

Tesla Model 3 / Y Performance: Uses "Track Mode" software to aggressively use the brakes to mimic a limited-slip diff.

Ford Mustang Mach-E GT: Uses brake-based vectoring to manage its high center of gravity.

Volkswagen ID.4 / ID.5 (GTX models): Uses "XDS+" electronic differential lock (brake-based).

Polestar 2 (Dual Motor): Primarily uses brake-based vectoring, unlike its larger sibling, the Polestar 3.

4. Mechanical Clutch Vectoring (The "Polestar" exception)

A unique middle ground where the car has two motors, but the rear motor is connected to two separate clutch packs rather than a standard differential.

Polestar 3: Uses a BorgWarner Twin-Clutch system on the rear axle. It can completely disconnect the rear motor for efficiency or use the clutches to send 100% of the rear torque to just one wheel.

REGEN

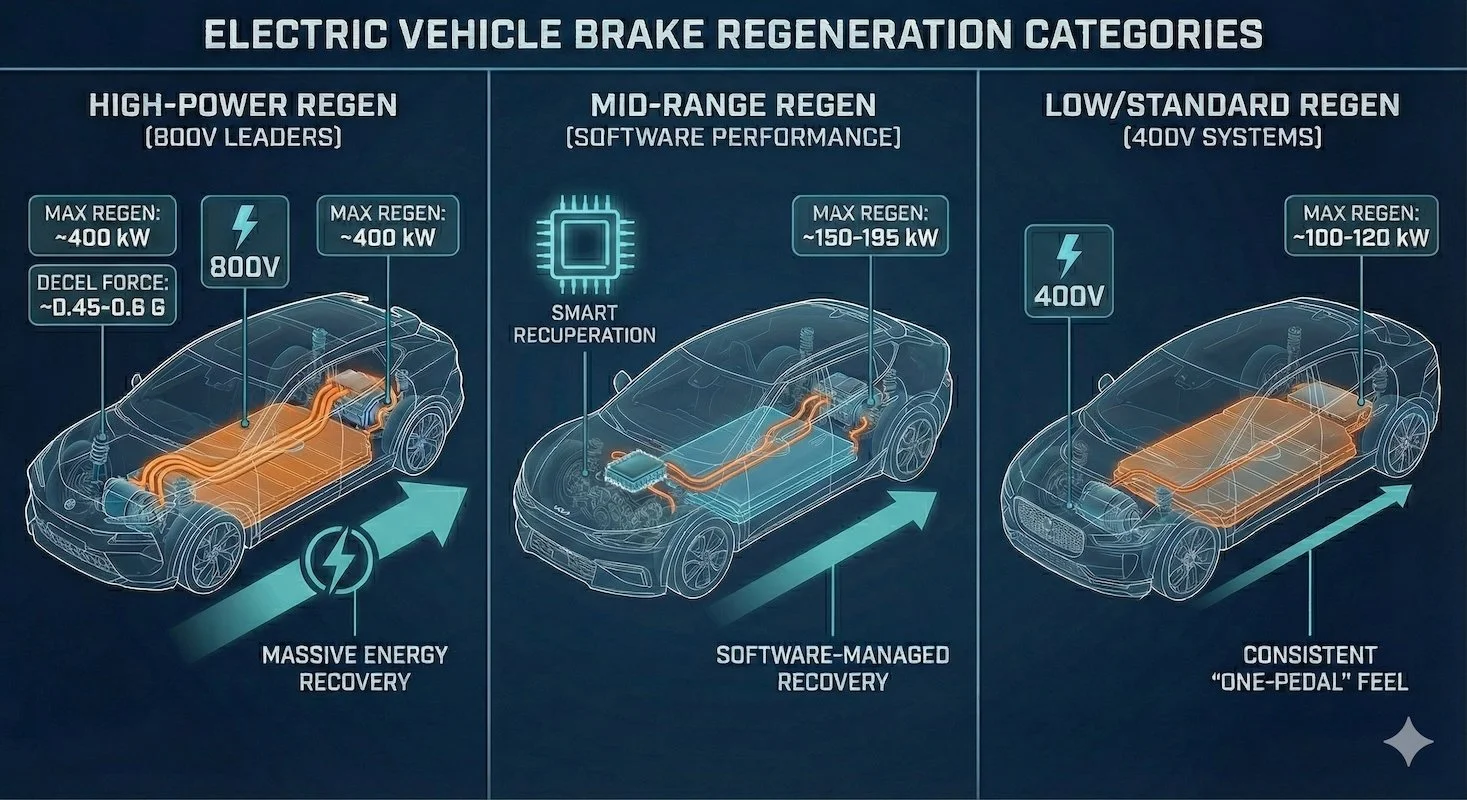

Brake regeneration is the "unsung hero" of EV performance. While a high-horsepower motor gets you to 60 mph, a high regen system determines how much of that kinetic energy you can "re-capture" rather than wasting it as brake heat

Here is the comprehensive list of AWD electric cars with their maximum regeneration power in kilowatts (kW), focusing on the highest-spec trim for each model.

1-High-Power Recuperation (The Leaders)

These cars are equipped with 800V architectures and advanced cooling, allowing them to suck in massive amounts of power during braking.

| Model | Max Regen (kW) | Deceleration Force | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Audi RS e-tron GT Performance (2025) | 400 kW | 0.45 G | The current industry leader in regen power. |

| Porsche Taycan Turbo S (2025) | 400 kW | 0.45 G | Shares its platform with Audi; uses the motors for 90% of all braking. |

| Hyundai IONIQ 5 N | ~260–300 kW | 0.60 G | While the peak kW is high, its 0.6G force is the strongest sensation in the industry. |

| Lucid Air Sapphire | ~300 kW | 0.35 G | High voltage allows for regen levels that match its ultra-fast charging speeds. |

| Mercedes-AMG EQS 53 | 300 kW | 0.30 G | Optimized for high-speed German Autobahn deceleration. |

| Rimac Nevera | 300 kW | 0.30 G | Massive 4-motor setup, but software caps regen to protect battery longevity. |

| Lotus Eletre R | ~250 kW | 0.30 G | Uses high-voltage architecture to maximize energy recovery during high-speed driving. |

2-Mid-Range Recuperation (Performance Software)

These cars have respectable regen but often rely on software "Track Modes" or blended braking to manage the energy flow.

| Model | Max Regen (kW) | Note |

|---|---|---|

| BMW i4 M50 / iX M60 | 195 kW | Uses “Adaptive Recuperation” that uses GPS/Radar to decide regen levels. |

| Kia EV6 GT | 150–180 kW | Similar tech to the Ioniq 5 N, but slightly less aggressive software. |

| Rivian R1T / R1S (Quad) | ~150 kW | Strong “One-Pedal” feel, but decelerative G-force is lower (approx 0.21G). |

| Maserati Folgore | ~150 kW | Focuses more on mechanical “engine braking” feel through software. |

3-Low/Standard Recuperation (The "Tesla" Approach)

Tesla and Jaguar favor a very consistent "One-Pedal" feel over raw peak kW numbers. While they feel strong at low speeds, their peak kW capacity is lower than the 800V rivals.

| Model | Max Regen (kW) | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Tesla Model S Plaid | ~100–120 kW | Limited by 400V architecture; “Track Mode” can increase this slightly. |

| Jaguar I-PACE | ~100 kW | One of the first to offer strong regen, but limited by older battery chemistry. |

| Ford Mach-E GT | ~100 kW | Aggressive feel in “Unbridled” mode but lower peak power recovery. |

| Polestar 2 (Dual Motor) | ~100 kW | Focuses on a smooth, linear transition between regen and physical brakes. |

WEIGHT & CG

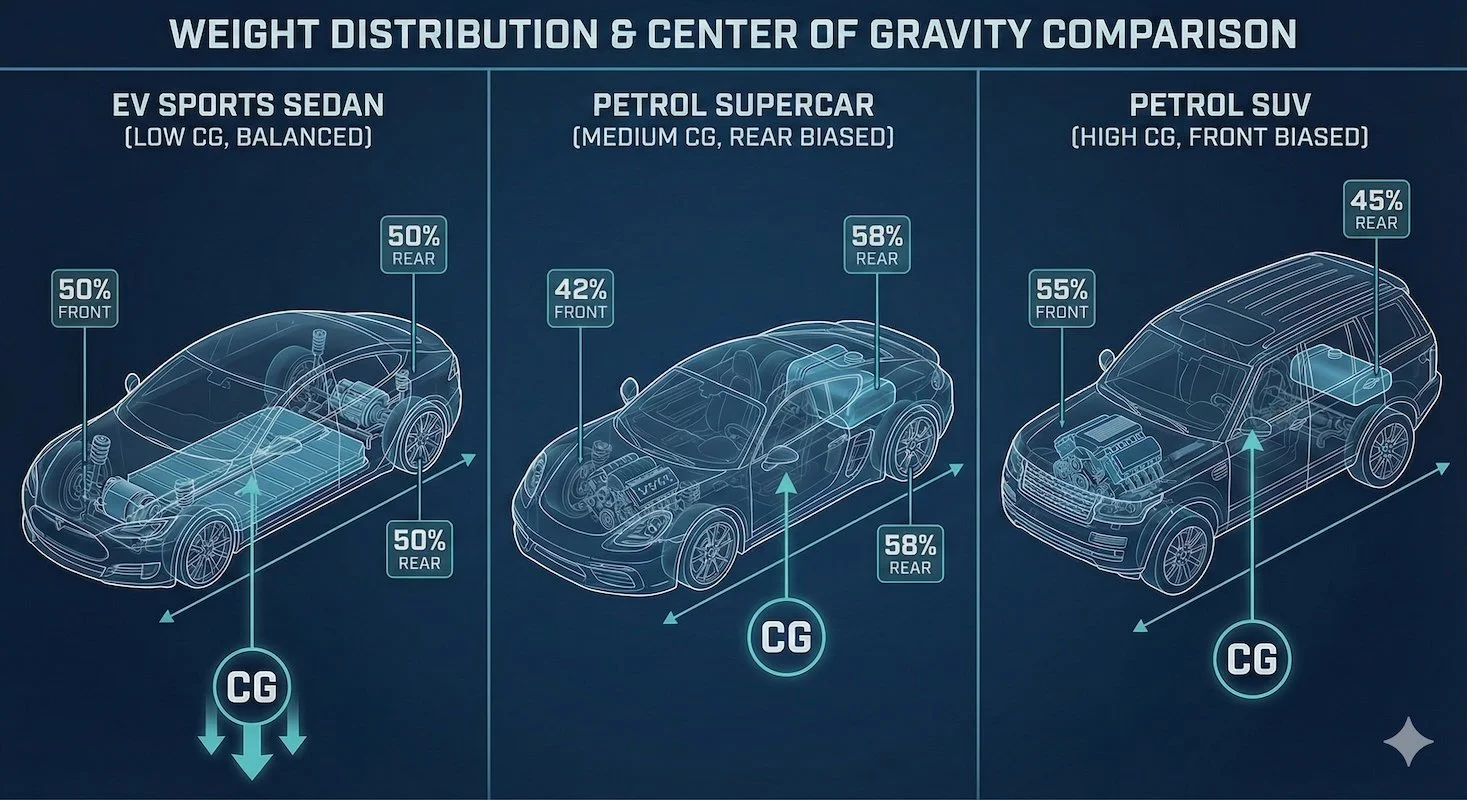

Rotational Inertia: Centering the mass between the axles (rather than over them) reduces the Polar Moment of Inertia, making the car easier to rotate into a corner and faster to stabilize during a slide.

Neutral Handling: A 50/50 balance ensures that neither the front nor rear tires are overloaded during a turn, preventing the natural understeer (pushing wide) found in front-heavy petrol cars.

Anti-Dive & Anti-Squat: The low center of mass reduces the weight transfer that occurs during hard braking or acceleration, keeping the car level and allowing all four tires to maintain a more consistent contact patch with the road.

Crash Energy Dissipation: Without a solid, incompressible engine block, the entire front of the vehicle can be engineered to collapse like an accordion, increasing the "stop time" of the crash and drastically lowering the G-forces transferred to the passengers.

Chassis Stiffness: In an EV, the battery pack is a "stressed member" of the frame. This makes the chassis significantly stiffer than a petrol car, where the engine is a dead weight sitting on mounts. High torsional stiffness means the suspension can work more accurately, providing better "turn-in" precision.

The "Frunk" and Polar Moment of Inertia: In petrol cars, the engine acts like a heavy pendulum at the front or middle. In an EV, that mass is spread between the axles. This reduces the Polar Moment of Inertia, meaning the car is easier to "spin" (rotate) into a corner and easier to "stop" from spinning (correcting a slide).

Regenerative Braking Precision: Unlike physical brake pads that can "grab" or "fade," regenerative braking is digitally controlled. This allows for ultra-smooth deceleration that doesn't upset the car's balance before a corner.

MODULATION

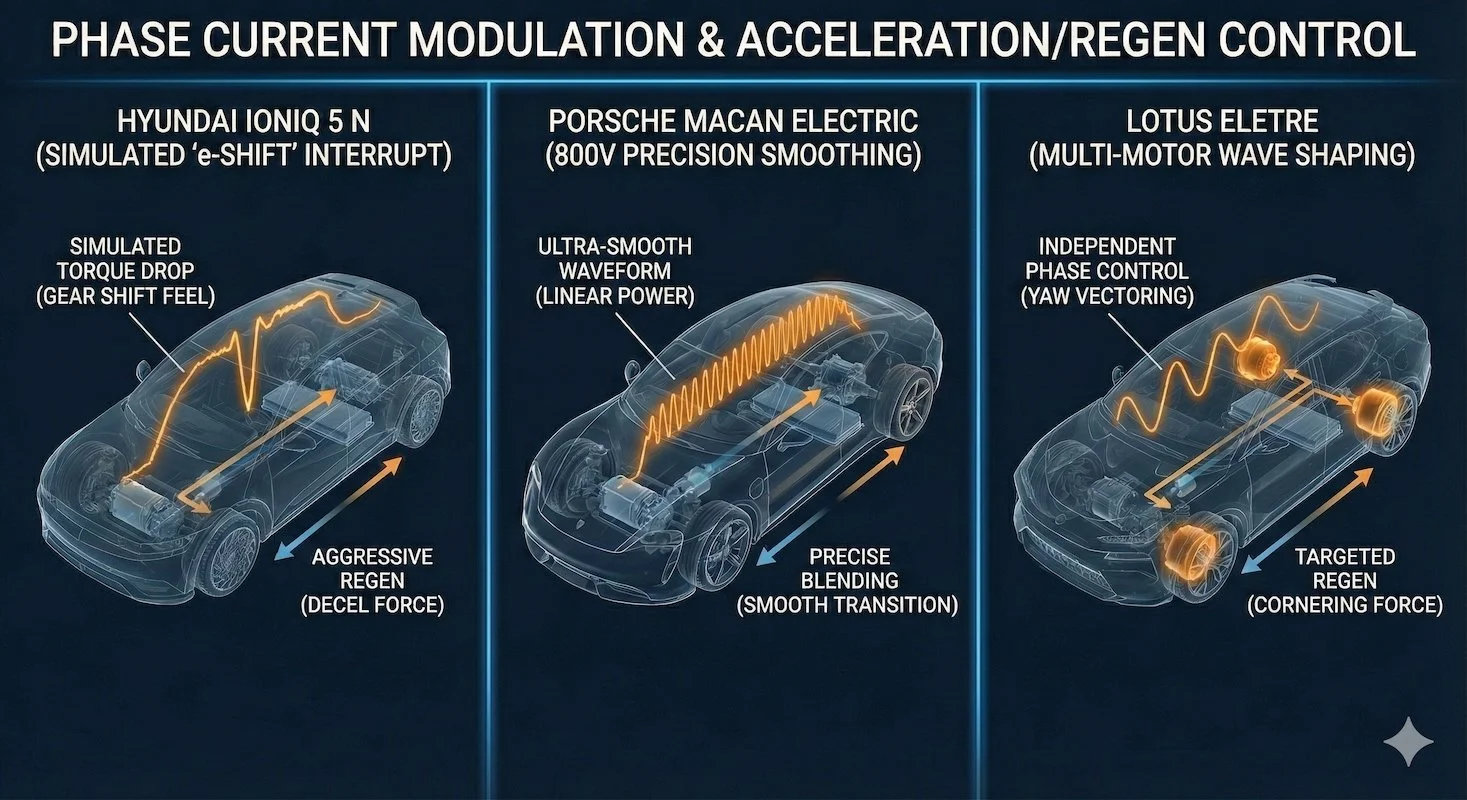

Manufacturers like Tesla and Hyundai (N Division) spend thousands of hours on throttle maps and downwards throttle modulation is a EV unique dynamic that can involve a lot of software and makes electric cars very versatile compared to the mechanically limited petrol counterparts

Phase Current Modulation is the digital "shaping" of electrical waves that allows an EV to transition from maximum propulsion to maximum energy recovery in less than a millisecond, providing the sensation of an instant, seamless gear change in both directions.

This modulation happens so fast (often at 10,000Hz) that the car can adjust the braking or accelerating force for every single inch of road surface, preventing skids before they even begin.

LATENCY & CD

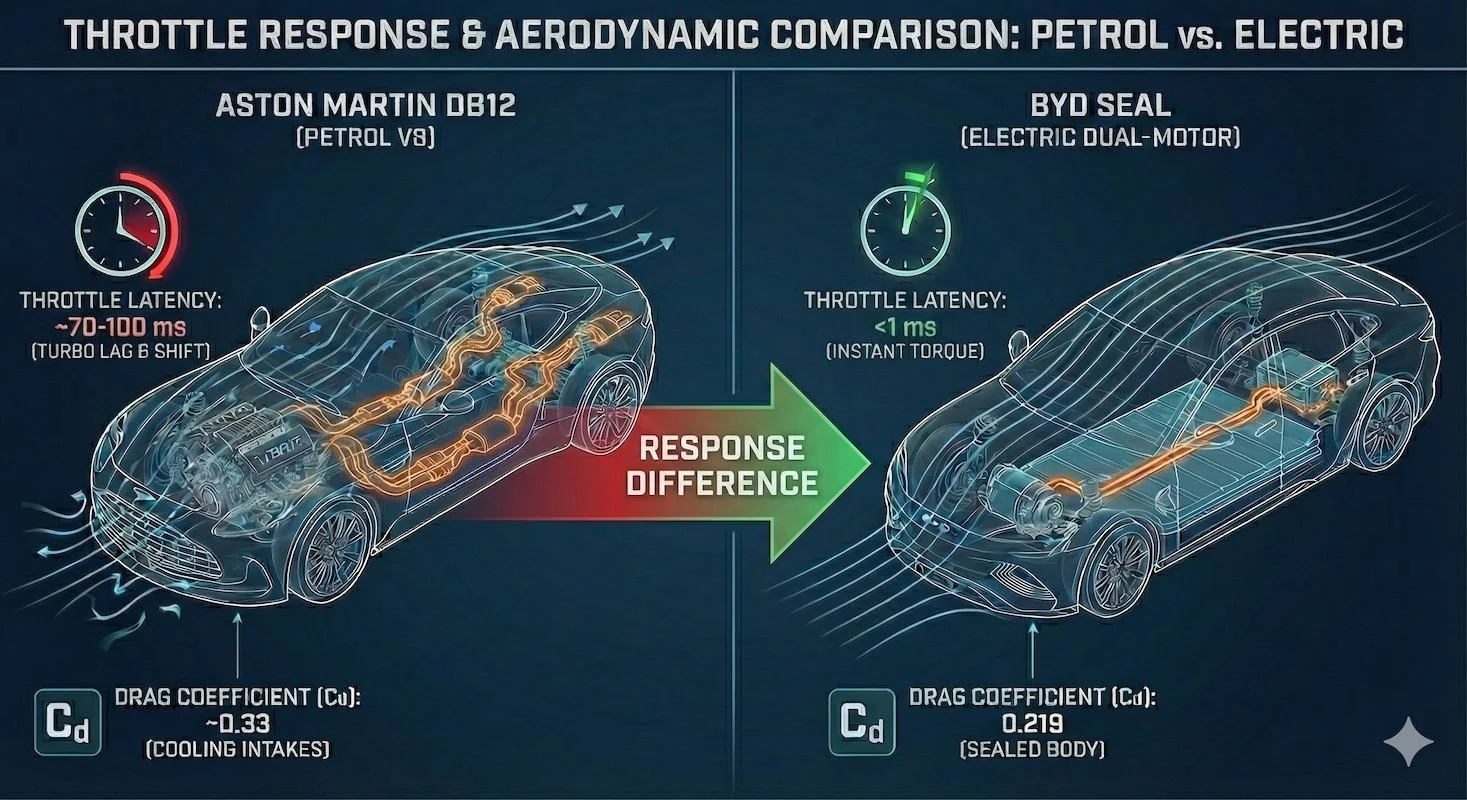

Latency (Throttle Response): A petrol engine must physically open a throttle plate, suck in air, inject fuel, and wait for a combustion cycle—even the best supercars have a 30–100 millisecond delay. An electric motor responds in less than 1 millisecond. This creates a "telepathic" feeling where the car begins to move the instant your brain decides to press the pedal.

As you push past 100 km/h (62 mph), the relationship between aerodynamics and the motor's inverter becomes critical:

Efficiency Gains: A car with a Cd of 0.219 (BYD Seal) requires roughly 30-32% less power to maintain high speeds compared to a car with a Cd of 0.32 (Aston Martin DB12). This "saved" energy can be re-routed by the inverter to provide a harder "punch" when you floor the pedal at highway speeds.

Thermal Headroom: Because the motor doesn't have to work as hard to fight the air, it generates less heat. This allows the Phase Current Modulation to stay at peak amplitude for longer periods before the car has to "throttle" power to protect the battery.

Regen Opportunity: Higher aerodynamic efficiency actually makes the "downshift" (regen) feel more pronounced because the car isn't being slowed down by the wind; instead, almost 100% of the deceleration force is coming from the magnetic resistance of the motors, allowing for better energy harvesting.

In conclusion electric performance is defined by a low center of gravity and balanced weight distribution, but true agility stems from advanced torque vectoring. While multi-motor hardware offers maximum precision, Phase Current Modulation enables "instant shifts" by reshaping magnetic fields in microseconds, allowing seamless transitions between propulsion and regenerative "downshifts." High aerodynamic efficiency (Cd) preserves this electrical energy for sustained high-speed acceleration by reducing wind resistance. Together, these digital systems transform EVs into telepathic performance machines, delivering a level of response and stability unattainable by traditional mechanical petrol drivetrains.